This review was written as part of KENS 5's 2020 San Antonio Film Festival coverage.

The first words uttered in “Higher Love” come from an unseen radio or podcast host proclaiming that “Camden is, for the rest of the country, a shithole.” The statement zeroes us in on what cityscape we’re gracefully observing from the night sky and will explore over the next 80 minutes. But the truth is the dingy street corners, haggard lots of overgrown weeds and cramped apartments that this solid (if slightly aimless) documentary on the drug overdose epidemic invites us into could belong to any American city—specifically, the parts of them left behind to corrode away under ever-widening socioeconomic gaps and consequences of negligence.

Hasan Oswald’s first movie – part of the 2020 San Antonio Film Festival’s lineup – is a dependable and narrowly focused diorama of drug addiction in urban America. “Dependable” is an adjective that doesn’t have to do much heavy lifting here; the stories Oswald captures don’t garner groundbreaking insight so much as the dreadfully familiar cycles of surrender to the needle, vocalizations of self-defeat and false starts on self-improvement that we’ve seen played out in all manner of storytelling from “60 Minutes” special to awards-bait Hollywood production (Remember “Beautiful Boy”?). We, of course, can’t hold that against Oswald—if there’s one thing the filmmaker gets across with his occasionally devastating observations in “Higher Love” (yes, he makes good use of the title’s double entendre) it’s that the possibility we’ll become numb to headlines of lower-class families destroyed by the influence of drugs is exactly the reason we need to continue seeing these stories, getting to know these people, sympathize with their struggles.

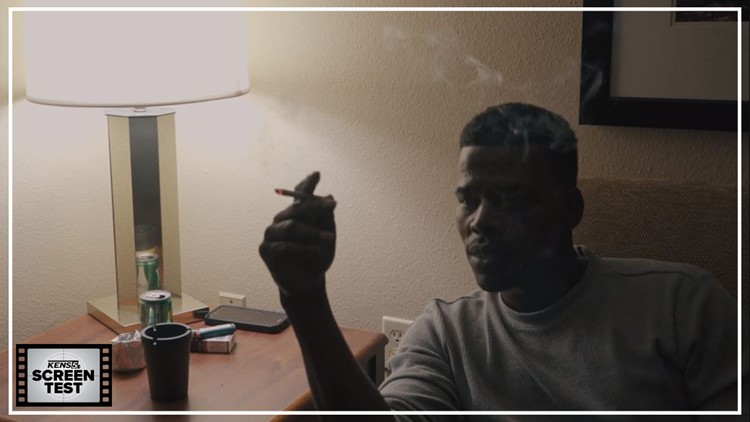

The struggles we see in Oswald’s movie are largely endured by Daryl and Nani, two Black residents of Camden, New Jersey for whom the latter’s need to throw her heroine dependence has never been more urgent—she’s expecting a child. They’ve been dealing with the effects of drugs on their relationship for so long that when we meet Daryl while searching for Nani in Camden’s run-down neighborhoods early on, it’s obvious it’s not the first time (and perhaps not the tenth) they’ve been through this. Oswald cuts from Daryl’s here-we-go-again eyes scoping out every alley to Nani barely able to keep her eyes open while she gets high and vents about her partner’s constant surveillance; it’s an engrossing way to start the movie, one whose structure is otherwise formal from here on out.

“If I wasn’t getting high, I’d probably be living it up right now,” the pregnant Nani confesses in tired croaks to the camera, to herself or to both. That serves well enough as the thesis of this sleekly shot and intimately rendered documentary, one that’s more interested in personal and interpersonal reckonings on self-control than in doing any exploring of the institutional causes of a drug crisis that killed 702,000 Americans between 1999 and 2017.

The film oscillates between spending individual time with Daryl and Nani as well as observing them interact with each other over the course of their journey. Promises of change are exchanged and thoughts wondered out loud about whether or not they’re taken seriously. We at times find ourselves thinking the same thing about the images that Oswald captures, and whether or not they cross a line into exploitation. Nani makes for a tormented subject – the kind of central figure these documentaries require – and more than once there’s nothing to do but watch her proclaim one intent while acting out another.

Daryl is by no means a saint either; his vice – at first alluded to before we see it for ourselves – is the bottle. And when we watch him work through the last drops of alcohol in one scene, just as disengaged and prone to slurring his words as Nani is when she gets high, “Higher Love” cuts to a familiar message with candor and clarity: Substance abuse is just a drop that leads to ripples of harm for the ones we care about the most.

Though “Higher Love” leaves empty some psychological crevices for deeper probing, it’s able to convey how users’ loved ones grapple with their roles in recovery—and the fallout of if they choose to leave when the burden’s become too much to bear. If the movie’s first half is about confrontation, it’s more interesting second half is about recognition, and finally action. Yet the parts of “Higher Love” that most immediately demand our attention are when Oswald captures the firestorms of curses and accusations and suppressed turmoil that erupt between boyfriend and girlfriend, father and son, brother and sister. The implosions are subtle.

And sometimes, regrettably, they’re not. One no-holds-barred moment is suppressed of its raw discomfort when, as Nani inserts a needle into her vein, “Higher Love” awkwardly overlays background audio of her child’s screams despite him being nowhere nearby. It’s a strange decision, as if Oswald was uncertain we’d understand the stakes. Elsewhere, the director employs a pair of kaleidoscopic montages that flash through images of law enforcement, funeral services, community sights and passionate spoken word, briefly pulling the lens much further back than Oswald has signaled he intends to. The sojourns are exhilarating, but last perhaps less than two minutes of screen time—so the emotion that lingers is confusion at how out of place they are in this version of a real-life drug addiction story. The sequences certainly indicate a bolder form of the genre than Oswald otherwise molds “Higher Love” into.

In one of the doc’s most transfixing moments, one of Nani’s so-called “get-high buddies” unleashes a monologue about togetherness, her words bordering on the philosophical. Documentaries naturally force us to consider the extent to which words and decision are informed by the presence of the camera that may turn a private space into a stage; here, that debate feels moot. As she outwardly laments the idea of getting high without Nani by her side, an evergreen sentiment rings clear despite the movie’s eventual untidy ending: Everyone is worthy of redemption. But they need to realize that for themselves.

RELATED: 8 movies for the uncertain moment